Our Normans of England: The Norman Invasion that Brought Them There

Email Webmistress**Copyright and Terms of Use**To Vol I: Our American Immigrants

The first Norman invasion can be considered Rollo's Norman Invasion of France ca 911; The Second the one here described and the third the Norman Invasion of Ireland starting 1169 and involving another of Rollo's descendants , the Earl of Pembroke living in Wales, & that man's also Norman and Rollo descended King Henry II of England.

Page Contents :

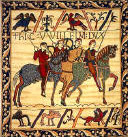

Wm the Conqueror, Duke of Normany,

brief intro

William's Norman Invasion

of England

and William's Domesday Survey of England

| William the Conqueror (see more

detailed bio) , GGG Grandson

to Rollo, the first Norman,was

born in Falaise,Normandy,France in 1028, son of Richard

II "the Devil" Duke of Normandy and his mistress Herleva

(Arlette). Their son was born within a year of the first meeting, and

their daughter Adeliza a few years later. In 1031 Robert married Estrith

(Margaret) Of Denmark, only to divorce that wife the following year.

As for Arlette, after her relationship with Robert ended, she married a

viscount of Conteville (Herluin) with whom she had many children,

including a son , Odo of Bayeux, who would figure important in the

history of William the king.

William's father died on return from pilgrimage to the holy land leaving young William to the care of gaurdians often forced to fear of their lives for the now duke's protection. His was a sad childhood hounded by would be killers and necessary, precipitous changes of locale . His adult family life was also tumultuous, involving armed struggle with sons and the imprisonment of family members. When 38 he raised the army that conquered England. The list of his direct ancestors up to Charlemagne offers a study of the substantiation and description of his ancestors there detailed. His wife' (Matilda of Flanders)'s ascendancy both paternally and maternally yields to the Capet Kings of France, and she too was Charlemagne's descendant. This couple had many children among whom are Adela of Blois and Richard Beauclerc, King of England, from each of which we can claim direct descent (See Wm the Conqueror's direct descent to our families in America ) . William long was forced to love of battle, and died not in the England he conquered but in the France of his birth. For bloating, heat and the peritonitis that took him, his body exploded when attempt was made to force him into his sarcophagus. His body has twice been disturbed in rebellions. A fuller description of his life and death are provided in his bio |

William's Seal.

|

The Norman Invasion of England .

Background:

England "The sister of the Duke Richard II of Normandy, Emma,

forged a crucial link between Normandy and England and between England

and Denmark. Firstly King Ethelred II of England married her in 1002 vainly

hoping to free his country from Danish invasion by being united to Normandy.

After his death in 1016, King Canute of Denmark and England, and son

of King Sweyn Forkbeard, married her in order to unite the Danish and Anglo-Saxon

dynasties. She produced kings from both marriages but her son, King Edward

the Confessor, from her marriage to King Ethelred contributed to causing

the Battle of Hastings. Edward the Confessor was brought up in Normandy

succeeded to the English throne in 1042 and re-established the Anglo- Saxon

dynasty after the Danish dynasty. Having been brought up in Normandy, he

spoke French and had learnt French customs and culture. When he came to

England, he tried to impose the French influence on the English and replaced

many of his advisers with French supporters and friends. This was counterbalanced

by the power of his English father-in-law, Earl Godwin" 3

who besides being father to Edward's wife, was father to Harold, king Edwards

advisor, the second most powerful man of the realm.

William, Duke of Normandy , was an illegitimate son of Duke Robert

I, and his grandfather, Richard II, Duke of Normandy was the brother in

law to Ethelred II. William believed himself the rightful heir to the british

throone.

In 1066, William Duke of Normandy, henceforth known as the Conqueror,

sailed across the English Channel from his duchy in France with an astounding

number of boats, filled with warriors and an unprecedented cargo: war

horses. Never before had an army set sail to England replete with this

powerful weapon. William came because England's king Edward the Confessor

had died that year, and he believed himself the rightful king.

In 1051 William visited King Edward the Confessor of England with whom

he shared a convoluted kinship in the far distant past. Edward was celibate

and childless, and promised to make William his heir---William said.

Then too there is the visit in 1063 or 64 to William in Normandy

by Harold Godwinnison, brother in law and trusted advisor to king

Edward of England and the 2nd most powerful man of the realm. The

circumstances of his arrival are unclear: he either went as emmisary of

the king or was blown off course and landed there. In any case, at that

time he was not apparantly easily allowed to leave, and William forced

him to swear on holy relics to support William's claim to the throne on

Edward's death. William also understood Harold to promise his own marriage

to William's sister Agatha (never accomplished) . Harold had become the

senior earl on his fatherís death, and increasingly took over the administration

and government of England whilst Edward The Confessor involved himself

more in church affairs, particularly the work with Westminster Abbey. By

1064 , Harold was designated ìDuke of the Englishî, tantamount

to heir apparent, but it did not imply succesion absolutely.

Harold was the son of the Earl of Wessex and Kent, and his mother was

a Danish princess. Many Nobles viewed him as a commoner and only noble

by marriage.

There were others who looked at the heirless king Edward and believed

themselves rightful claimants by blood, but Edward had yet to name a succesor

at the time he took to his death bed. The king did not support the claim

of the young Edward the Aetheling, and it very questionable indeed that

he ever would have supported William, Norman to the core and culturally

alienated from the people of England.

In 1066 it is purported that the king whispered "to Harold" in

dying breath, thus passing the kingdom. Whether or not the king did name

him, Harold was a logical choice for England. His powerful position, his

relationship to Edward and his esteem among his peers all recommended him

to the kingship, and the Witan (royal advisors representative of

all the realm) supported the choice. He was crowned on the day Edward was

buried.

The kingship was not one to which Harold had obviously aspired; He

was greatly powerful, extremely competant, and very comfortable in his

role as King's advisor. Evidence suggests Harold to be a man of conscience

and immense politcal savvy. He would likely have served loyally and usefully

to another king, had another good choice been named by his predecessor.

And, had he lived, he may well have been among England's finest kings.

The culture of Normandy differed greatly from that of England: Rule in Normandy was a birth right and no council equivalent to a witan existed in the realm of France. Rule in England involved a king's right to name his succesor and the need of the Witan, representative of the entire realm, to support the king's choice or present alternative. William was certain of his right.

Subsequent to Edward's death, letters from an angry William passed to

Harold across the channel. Reminders of promises extracted were forbodingly

referred to. Harold , now King Harold II , anticipated William's

invasion. He amassed an army and camped for months on England's southern

coastline, awaiting an attack from across the Channel he was certain would

manifest, but that never came. The season for safe crossing passed. Harold

felt himself and England secure, at least until next year. Harold

sent the army home to the fields and families long now in need of them.

| On the other side of the channel William had built hundreds of ships

for the army he ammased to take to England. The winds blowing in the channel

frustrated him; For months the Norman Duke was poised to sail, but

the winds did not blow to his favor. He could not afford to accomodate

oarsmen. His boats, like all of Northern Europe of the time, were

without rudders, reliant on a sail's response to unharnessed wind with

destinations more hoped for than able to be controlled. They were like

toy boats a child places on a pond, reliant on the direction of a wind

for the destination they will find, and the smarter child learns

to read the wind in order obtain his desired end point. He and Harold both

knew the season's wind should have been in William's favor. But for months

it was not. William, holding his army ,still waiting for the right wind,

found his warriors frustrated and threatening abandonment of the endeavor.

The traditional season for safe crossing passed. But then the

wind shifted. Recognizing that he could not wait another year and

hope to have an army as powerful as this one, he called the army

to boats and sea. The warriors, having nearly abandoned him

in the days before agreed to the ride and battle recognizing the possibility

of enormous wealth the undertaking represented. William did

what noone else had done before. He assured sufficient boats to accomodate

the warriors AND their war horses

, and set sail across the channel in a time frame not before undertaken.

When William arrived, Harald had already released the army poised in

England's south, only to recall them when caught off gaurd by an

invading army to the north led his brother Tostig and Harold III Hardraade

of Norway, who claimed the throne. He rushed off and defeated them at Stamford

Bridge (1066). No sooner done with this danger, he learned of William's

landing to the south with an astounding number of ships and warriors accompanied

by an unprecedented and deadly cargo: their War Horses. He rushed

off to meet this 2nd invading army of his brief reign, and was killed in

the battle of Hastings, struck with an arrow through the eye, his

body dismembered on the field. The unexpected timeframe for arrival , and

unprecedented transport of warriors with war

horses, can not be overstated regarding the battle's outcome. William

went on to conquer Canterbury, Winchester and London. The Duke of Normandy,

now 38, with a horrendous childhood behind him, had raised the Norman army

that conquered England and was the first of its long line of Norman kings.

William introduced the act of Beheading to England and he brutally subjugated

England. Among those who suffered was the man his wife first refused him

for, named Brihtric, who was thrown into a dungeon where he died.5

For an Account of the Battle of Hastings, see BBC's Norman Conquest

Pages and the

Battle of Hastings within them

|

|

| There are some 13418 towns and villages recorded in the Domesday Book,

covering 40 of the old counties of England. The majority of these still

exist in some form today.

"During the last years of his reign, King William (the Conqueror) had his power threatened from a number of quarters. The greatest threats came from King Canute of Denmark and King Olaf of Norway. In the Eleventh Century, part of the taxes raised went into a fund called the Danegeld, which was kept to buy off marauding Danish armies. One of the most likely reasons for the record to be commissioned was for William to see how much tax he was getting from the country, and therefore how much Danegeld was available. Each record includes, for each settlement in England, its monetary value and any customary dues owed to the Crown at the time of the survey, values recorded before Domesday, and values from before 1066. The Domesday survey is far more than just a physical record though. It is a detailed statement of lands held by the king and by his tenants and of the resources that went with those lands. It records which manors rightfully belonged to which estates, thus ending years of confusion resulting from the gradual and sometimes violent dispossession of the Anglo-Saxons by their Norman conquerors. It was moreover a 'feudal' statement, giving the identities of the tenants-in-chief (landholders) who held their lands directly from the Crown, and of their tenants and under tenants. The fact that the scheme was executed and brought to complete fruition in two years is a tribute of the political power and formidable will of William the Conqueror." Image right and the text above are from The Domesday Book on Line |

aaa |

Footnote One

Warhorses of the Midieval Era

"It is commonly believed that the great war-horses, also called destriers,

were developed during the Middle Ages to support the great weight of the

armored knight. Actually, a good suit of armor was not over 70 pounds in

weight; and therefore, the horse would only be expected to carry some 250

to 300 pounds. The real reason large horses were useful was because their

weight gave greater force to the impact of the knight's lance, both in

warfare and in the tournament. A destrier weighed twice as much as a conventional

riding horse; and when the knight struck a conventionally mounted opponent,

the impact could be devastating. The destrier was sometimes shod with sharp

nail heads protruding so that he could trample foot-soldiers in his path.

The destrier was a very potent weapon, and yet his descendants are the

mild mannered and docile work horses of today who put their strength to

less brutal use. "

From Midieval

Horses presented at the Museum of the Horse's website pages involving

A

Chronological History of Humans and Their Relationship With the Horse.

3 BBC History , the Battle of Hastings