Military Actions of the Powhatan Confederacy

Home **Copyright &Terms of Use**Email Webmistress

Military Actions of the Powhatan Confederacy Home **Copyright &Terms of Use**Email Webmistress |

| Introduction

to Topic:

The1st Anglo Powhatan war did not involve forebears within these pages, being initiated in 1610 during the reign of Powhatan, and ending more or less with the marriage of Rolfe and Pocahontas in 1614, after which was a tenous peace ended by the death of Pocahontas in England in 1617 and her father, the Chief in 1618. The event sparking the 2nd Anglo Powhatan War [1622-1632] occured in the expertly mounted Good Friday Massacre/Action, five years after the arrival of our Piersey forebear in 1616, three years after our Woodson forebears arrival in 1619, and four years after the ascendancy of Powhatan's half brother Openchancanough. Although foiled and not entirely succesful, The Good Friday Action is perhaps, the most succesful attack against European incursionists in all of Native American History. The 3rd Anglo Powhatan War [1644-1646] was ignited by the massacre of 1644 in which our forebear Dr John Woodson was killed while his wife and two sons survived. Although more people died in that attack than in the first massacre, its effect on the colony was not as great, the percentage of victims being diminished over that of the massacre/action of 1622 which nearly destroyed the colony. The first Anglo Powhatan War can be viewed as an attempt at subjugation of the enemy by both sides. The Second War was ignited wtih intent to exterminate the British colony, and harvested nascent attempts at extermination of the Indian. The Third war resulted in the capture and death in Jamestown of Chief Opechancanough. Its end involved formal separation from white settlements and the advent of the reservation system well known to modern Americans. |

|

|

(For Background to this Subject, See The Powhatan Confederacy , Chief Powhatan [reigned before 1606-1618] and Chief Opechancanough [reigned 1618-1644]). Chief Opechnacanough has perhaps the most interesting history of any person found in these pages.

|

||||

|

For Background to the Following , See: The Powhatan Confederacy Pages , and within them Chief Powhatan and His Reign Pre and Post Contact up to The First Anglo Powhatan War also, The Page Dedicated to History of the Jamestown Colony After years of fractuous coexistence, occasional trading, parlays, actions and retribution, despite the arrival of colonists aboard two ships built from the remains of the former flag ship Sea Venture from Bermuda where it had been shipwrecked, and as a result of being completely worn down by the starving time of the winter of 1609-1610, the desperate English settlers decided to abandon the colony of Jamestown on May 20 and set out back to England.

With the return of the English, Powhatan continued to harrass the settlers, and the English responded by ambushing the Kecoughtans and taking their land. In July a message was sent to Powhatan offering peace or war, and the terms of peace were described [return our captives amongst you and all stolen goods immediately] . Powhatan refused the terms and offered some of his own [Go back to England this instant or stay in your fort at your peril; To come out is your death]. "The First Anglo-Powhatan War was the result of Lord de la Warr's orders to George Percy on August 9, 1610. Percy and seventy men went to the capital town of Paspahegh where the English killed or injured fifty or more people and captured a wife of Wowinchopunch, the weroance of the Paspahegh [ed note: a member tribe of the Powhatan Confederacy] , and her children. After returning to their boat, the Englishmen killed the children by throwing them overboard and shooting them in the water. The killing of women and children was not tolerable in Powhatan warfare: it greatly affected Powhatan and his people. The Paspaheghs never recovered from this and appeared to have merged with other chiefdoms."19 "Powhatan .... warriors harassed the colonists with small-scale attacks. Although the colonists eventually planted their own corn, they remained dependent upon the Indians to ensure that they would have enough provisions, especially in the lean winter months. Powhatan continued to trade but the terms became more contentious. In 1614 [ed note: some sources say 16143, some 1613, this encountered discrepancy is probably a result of the change in calendar occuring in the later part of 1700s and itsaccomodation or lack of it ] , the Englishmen kidnapped his daughter Pocahontas [ed note: Princess Matoaka] in order to get back some of their own people taken in the attacks. The settlers offered a prisoner exchange and Powhatan complied with this request. He refused, however, to return the stolen weapons that the colonists demanded." 20 Pocohontas was christianized during the period of her capture, and is said to have requested of her father to marry John Rolfe, to which Powhatan, worn down by war, as were his adversaries, agreed. It was the marriage of Pocohontas to John Rolfe the year following her capture which allowed a period of peace. Pocohontas' groom Rolfe was a recent widower and Pocahontas his second wife. The dtr of Rolfe's first marriage, named Bermuda, for the island on which she was born , died there also. Her parents and all passengers of the flagship Sea Venturehad been temporarily shipwrecked there. Rolfe's first wife is thought to have died soon after her arrival with Rolfe to Jamestown on the remains of the Sea Venture resurrected in two new ships . Pocahontas,despite her tender age [17 at the time of marriage to Rolfe] is sometimes said also to been married before, to a native American with whom at the time of her marriage to Rolfe, she was still allied , he being " an Indian named Kocoum, whom she supposedly married in 1610. It is not known whether this accusation was truthful or created by an enemy of Pocahontas. "22 The marriage of Rolfe and Pocohontas allowed for a period of relative peace and tranquility for both the Powhatan peoples and the English colonists. Pocohontas, renamed Rebecca in the English community, bore a son in 1615. In 1616, she , her husband, and theirinfant son Thomas Rolfe, in company with 10 other Indians, embarked to England where Pocohontas died in 1617. John Rolfe returned to Virginia that same year. Back in Virginia John Rolfe married " Joane, the daughter of William Pierce, who had come to Jamestown in 1609. Rolfe made out his will in 1622, confessing to being ' sick and weak in body' "21 See Footnote One for the legacy of John Rolfe and his son in Virgina. Powhatan himself died in Virginia in the month of April, 1618, one year after his daughter. Initially King Powhatan was succeeded by brother Opitchanpan but for just a few months19 That supreme Chief stepped aside in favor of Opechancanough, chief of the Pamunkey and another half brother of the dead Chief Powhatan. Opechancanough was far more militant than his dead half-brother Chief Powhatan, and had been responsable for John Smith's early abduction during the reign of his brother, in which scenario Pocohontas is sometimes said to have intervened. Opechancanough became the leader of the Powhatan and he radicalized his people. The fragile peace inspired by Rolfe and Pocohontas' marriage in 1614 was entirely fractured in 1622. The English killing of Nemattanew , a revered and popular native spiritual leader, was the rallying call required by a Powhatan Chief intent on war and, soon after, Chief Opechancanough mounted the expertly orchestrated Good Friday Massacre. This action was nearly succesful in its aim to permanently drive the English from Powhatan territory and its result was the decade long Second Anglo Powhatan War . Chief Opechancanough survived the 1st and 2nd Anglo Powhatan Wars, and he lived to orchestrate another massacre in 1644-an attempt to stem at best, and overcome if possible, the humiliation and defeat the Powhatan suffered with the 2nd Anglo Powhatan War. The 1644 massacre initiated the Third and final Anglo Powhatan War but this great chief would not see the last wars conclusion, for he was captured and died in Jametown in 1646. The last war resulted in the first reservation endured by the AmerIndians in the region which would, in its future, be known as the United States.

To Top of Topic: The First Anglo Powhatan War |

||||

Top of Page The Second Anglo Powhatan War

From 1618 there was a movement among certain of the [Virginia] company to incorporate the Indians into the society, to christianize them, and some were living in the town. Still the colonists in general disdained the natives, seeking to change them, not fully recognizing as full fledged members of the community , and not fully trusting them. But "Before the attack on March 22, 1622, the Powhatan people were free to come and go in the English settlements. They were free to borrow tools and even boats. George Thorpe, an English minister and new governor, believed that the Powhatans were 'of a peaceable and vertuous disposition' and treated the Powhatans kindly. This attitude spread to other colonists, giving the Powhatans mixed feelings."19 Opechancanough's gathering fury and his attempt to obliterate the colony can be described in sociologic terms as an attack on cultural deconstructionism as much as protection of territory . This great leader of his people had reason to object to the amalgamation of his race into the Jamestown populace and religion; The amalgamation attempts by the colonists weakened the Chief's dependance on his people's loyalty, but far more powerfully than he anticipated. "Opechancanough expected help from every warrior in every tribe in the planned attack. "19 " Powhatans who were torn in their loyalties were personified in a legendary figure known as "ChancoFootnote 1 ." 19 who, at the last hour, thwarted the complete destruction planned by his Chief., warning Mr Pace, who in turn warned Jamestown. The massacre , remarkably well planned and executed, was unable to destroy Jamestown, although great destruction was done to its outlying villages. Had Chanco or Pace not alerted the Jamestonians, the attack would probably show in history as a complete Powhatan success. Despite his Christian training under the Spanish, Opechancanoughís one goal was to drive the English from Virginia. Toward that end, he organized and executed the terrible massacre of Good Friday, 22 March 1622. Three hundred forty-seven men, woman and children were murdered and mutilated with their own weapons. This loss represented one-third of the colonyís population." 8 Backgound to The Trouble leading to the Massacre This unsourced entry appears to be from an unidentified text and is presented at Sue Gill's Webpages, with citation: ' Submitted by PACJ1945@aol.com on VA Southside Mailing List, submitted for Gill web page by Sue Gill' . Despite being unsourced, the contents bear review. The reader is strongly encouraged to access the original page at Sue Gill's Webpages. If anyone recognizes the text, please inform " Disregard for the aboriginal occupants of Virginia called forth anew the question of 'right and title,' a problem subject to discussion in England even before Jamestown. To allay these attacks, several proponents of colonial expansion attempted to justify the policy of the crown and the London Company. " Sir George Peckham in ' A true reporte of the late discoveries' pointed out as early as 1583, relating to the discoveries of Sir Humphrey Gilbert, that it was ' lawfull and necessary to trade and traficke with the savages.' In a series of subsequent arguments, he then expounded the right of settlement among the natives and the mutual benefit to them and to England. This theme was later extended by the author of 'Nova Britannia', who maintained that the object of the English was to settle in the Indian's country, 'yet not to supplant and roote them out, but to bring them from their base condition to a farre better' by teaching them the 'arts of civility.' The author of ' Good Speed to Virginia' added that the 'Savages have no particular propertie in any part or parcell of that countrey, but only a generall residencie there, as wild beasts have in the forests.' This last opinion, according to Philip A. Bruce, prevailed to a great extend and was held by a majority of the members of the London Company in regard to the appropriations of lands. "In spite of these views entertained by the company, there were several instances in which the natives were compensated for their territory. This was done primarily through the initiative of local authorities, for they were usually better informed concerning Indian affairs. They were in much closer contact with the natives than the company's Council in London and realized that the goodwill of the aborigines could be cultivated by giving only minor considerations for the land occupied by the English. On other occasions the Indians voluntarily gave up their land such as the present from Opechancanough in 1617 of a large body of land at Weyanoke. At still other times land was seized by force. When any attempt was made to justify the seizure, it was done on the basis of an indemnity for damage inflicted upon the colony or for violations of agreements by the natives. By 1622 settlements had been made along the banks of the lower James River and in Accomac on the Eastern Shore, the land having been obtained by direct purchase, by gifts from the natives or by conquest. " Any attempt to determine the extent of the areas acquired by purchase in Virginia is hindered by the indefinite nature of the Indian holdings and by the lack of complete records for the early periods. Thomas Jefferson thought much of the land had been purchased. Writing to St. George Tucker in 1798, Jefferson stated: " ' At an early part of my life, from 1762 to 1775, I passed much time in going through the public records in Virginia, then in the secretary's office, and especially those of a very early date of our settlement. In these are abundant instances of purchases made by our first assemblies of the indi[ans] around them. The opinion I formed at the time was that if the records were complete & thoroughly searched, it would be found that nearly the whole of the lower country was covered by these contracts.' " Jefferson overestimated the amount of land that was purchased by Virginia during the early years. While the records now extant show that the colony often purchased lands, they likewise indicate that frequently land was appropriated without compensation. Especially during the years following the first massacre of 1622, ' The Indians were stripped of their inheritance without the shadow of justice.' The greater part of the Peninsula between the York and James rivers was taken by conquest; the right of possession was later confirmed by a treaty with Necotowance in 1646, without, however, any stipulation for compensating the natives for the land they relinquished. " 23 Top of Page [The Anglo Powhatan Wars] Top of Topic [The 2nd Anglo Powhatan War] On to: The The Massacre/Action of 1622 as reported Contemporanously to the English The Second Anglo Powhatan War The Massacre as Reported to England Contemporaneously and in 1622

Footnote

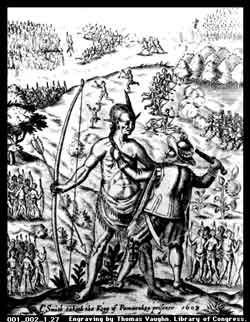

1: Clarification of the Powhatan Leader mentioned at the time of

this massacre:

The Writer is calling the King of the Powhatan's not by his name, but by his title, similar to The King of England without reference to the Christian name of the king at the time. The leader of the Powhatan Confederacy at this time was Openchanacough succesor and younger brother to Wahunsonacock. The English did not call Wahunsonacock by that name, but referred to him as King Powhatan. This writer seems to be continuing the tradition. Top of Topic [The 2nd Anglo Powhatan War] On to: Retaliation and the 2nd Anglo Powhatan War Realized

Retaliation and the 2nd Anglo Powhatan War Realized "The surviving settlers' reaction to the Powhatan uprising was retaliation, and the English, better armed and organized than the Powhatans, set to with a vengeance. The Virginia Company instructed the settlers to wage a total war against the Powhatan people, doing whatever it took to subdue them utterly. For over a decade, the English killed men and women, captured children and systematically razed villages, seizing or destroying crops. After the uprising, the colonists recovered & expanded their territory, even as the Powhatan empire declined both in power & population"9 In late June or early

July 1622, Captain Smith was aware of survivors of the March 1622

massacre, and that Mistress Boyse and 19 others were held captive near

present-day West Point, Virginia. 1 These

captive women [the male captives above had all been killed] were in a constant

state of jeapordy, "Lodged as they were with Opechancanough, the prime

target of retaliation, [they] like their captors, endured hasty retreats,

burning villages, and hunger caused by lost corn harvests. " 1

The retalitory raids of that summer forced Opechancanough to negotiation,

and the women were used to that end. "In March 1623, [Openchancanough]

sent a message to Jamestown stating that enough blood had been spilled

on both sides, and that because many of his people were starving he desired

a truce to allow the Powhatans to plant corn for the coming year.

In exchange for this temporary truce, Opechancanough promised to return

the English women. To emphasize his sincerity, he sent Mistress Boyse

to Jamestown a week later. When she rejoined her countrymen she was dressed

like an Indian ìQueen,î in attire that probably would have included

native pearl necklaces, copper medallions, various furs and feathers, and

deerskin dyed red. Boyse was the only woman sent back at this time, and

she remained the sole returned captive for many months. For the present,

colony officials felt that killing hostile Indians took precedence over

saving English prisoners, and they never intended to honor the truce

in good faith. However, the Powhatans were allowed to plant spring corn

to lessen their suspicions 'that wee may follow their Example in destroying

them'

These raids

against the Indians helped to heal the emotional wounds of the colonists,

but victory came at a high price. While the captive women suffered alongside

their captors, the Indian war transformed the colony into an even cruder,

crueler place than before. The war intensified the social stratification

between leaders and laborers and masters and servants, while a handful

of powerful men on Virginia Governor Sir Francis Wyattís council thoroughly

dominated the political, economic, and military affairs of the colony.

" 1

For

majority of the text in this topic See "Martin's

Hundred By J. Frederick Fausz for American History Magazine

Found at HistoryNet.Com Footnote

One, A Female Survivor of Martin's Hundred Likens Jamestown post her capture

to her captivity: Dr James

Pott , famed Jamestown Surgeon intimately involved in the governance of

the colony eventually paid ransom for the freedom of Jane Dickenson, whose

husband's indentured servitude had been cut short by the massacre. In very

short time she petitioned for her freedom from him,describing his treatment

as no better than the slavery she had endured among the Indians.

See "post massacre census 1623, and the women of Martin's Hundred" . To Top of Topic and its own Table of Contents [the 2nd Anglo Powhatan War] On to The 1632 Treaty ending the 2nd Anglo Powhatan War The Following is

fromîThe

Pamunkey Davenport Chroniclesî by John Scott Davenport, Ph. D.

Margo McBride Editor. Crystal Lake, Il 60014.

"Pamunkey Neck, that long finger of land between the Mattaponi and Pamunkey Rivers above where they join to become the York River (in 2001 King William County, the southern half of Caroline county, and southernmost Spotsylvania County), was set off by Treaty between the Governor of Virginia and the King of the Pamunkey Indians in 1623. The Pamunkeys (of Pocahontas fame) were the largest and strongest of all the tribes in Powhatanís Confederation opposing English settlement and exercised the major role in the Massacre in the English Settlements on Good Friday, 1622. Their pacification was imperative if Virginia English settlement was to succeed. By the Treaty of 1632, Pamunkey Neck was declared to be an Indian reserve, protected from settlement or hunting trespass by the English. There was , in fact, a mandatory death sentnce in place until 1648 for any White Man caught settling or trespassing in the Neck. But the Pamunkey King himself began to make exceptions, needing help from the English and their muskets to drive off raiding Senecase from the North, the fierce Tuscaroras from the South, and other nomad tribes of Iroquoian stock who kept the Neck in turmoil (the Pamunkey and their allies were of Algonquin roots.) The Indian King allowed so mny White Men into his preserve-their only bar was that no English settlement be within three miles of an Indian town-that Virginia authorities recognized that the Pamunkeys bey their self serving allowances had made the death penalty a face.Then too, the tribeís repeated attacks upon settlers bordering the Neck had created a demand among settlers that the Pamunkeys and their allied tribes be pacified by being made civilized, which required close interface between the Indians and the English. The death sentence relative to settlement and hunting in the Neck was repealed in 1648.The Third Anglo Powhatan War [1644-1646] The Treaty of 1646 ending the Third Powhatan War 1.What the Treaty of 1646 Sought 2. The Lands Involved in the 1646 Treaty"The treaty of 1646 with the successor of Opechancanough inaugurated the policy of major historical significance of either setting aside area reserved for Indian tribes, or establishing a general boundary line between white and Indian settlements. Influenced by the desire of individual settlers to fortify their claims and by the opposition of the natives to white encroachment, the colony designated definite lands for the Virginia Indians and began to follow more closely the custom of purchasing all territory received from the natives. To see that this was done, the Assembly passed numerous laws, pertaining in most cases only to the specific tribes of Indians mentioned in each act.... The treaty of 1646 designated the York River as the line to separate the settlements of the English and the natives. But the colony at that time was on the eve of a great period of expansion. With an estimated population of 15,000 in 1650, the colony increased by 1666 to approximately 40,000, and by 1681 to approximately 80,000. To stem the tide of the advancing English settlement was apparently an impossibility. Therefore, Governor William Berkeley and the Council, upon representation from the Burgesses, consented to the opening of the land north of the York and Rappahannock rivers after 1649. At the same time the provision making it a felony for the English to go north of the York was repealed. "Before Surry was split from James City, the settlers made the first of many treaties with the Southside Virginia Indians. It appears that the Southside tribes of Indians were relatively weak, and hardly had enough warriors to protect themselves. This treaty provided help from the settlers, should other marauding tribes of Indians attack them.The Effects of the 1646 Treaty [from "Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century:An Inquiry into the Material Condition of the People, Based on Original and Contemporaneous Records. by Bruce, Philip A. New York: MacMillan and Co., 1896. Chapter VIII, p 491-492 [cites 1 Abstracts of Proceedings of the Virginia Company of London, vol. II, p. 6.] "The larger proportion of the Peninsula, the seat of the earliest English settlements, was acquired at first by conquest, but right of possession was afterwards confirmed by treaty. Thirty-nine years after the foundation of Jamestown, in a conference between Necotowance, the new Indian ruler, and representatives of the colonial government, the former, in the name of his people, agreed to abandon all that area of country which extended between the James andYork from a line drawn from the falls of the Powhatan to the falls of the modern Pamunkey. No attempt was to be made tdisturb their tenure of the region lying between the York and Rappahannock. If any one of the colonists visited the north side of the former stream without having been driven across by stress of weather, or having gone thither for the purpose of gathering sedge, or cutting timber, he was to be considered a felon and punished as such. Necotowance was required to acknowledge that he held his kingdom under the authority of the sovereign of England.1This unsourced entry is presented at Sue Gill's Webpages, with citation: (Submitted by PACJ1945@aol.com on VA Southside Mailing List, submitted for Gill web page by Sue Gill) . Despite being unsourced, the contents bear review. The reader is strongly encouraged to access the original page at Sue Gill's Webpages. "The treaty of 1646 with the successor of Opechancanough inaugurated the policy of major historical significance of either setting aside area reserved for Indian tribes, or establishing a general boundary line between white and Indian settlements. Influenced by the desire of individual settlers to fortify their claims and by the opposition of the natives to white encroachment, the colony designated definite lands for the Virginia Indians and began to follow more closely the custom of purchasing all territory received from the natives. To see that this was done, the Assembly passed numerous laws, pertaining in most cases only to the specific tribes of Indians mentioned in each act. " In 1653 the Assembly ordered that the commissioners of York County remove any persons then seated upon the territory of the Pamunkey or Chickahominy Indians. At the same time both lands and hunting grounds were assigned to the red men of Gloucester and Lancaster counties. The following year the Indian tribes of Northampton County on the Eastern Shore were granted the right to sell their land to the English provided a majority of the inhabitants of the Indian town consented and provided the Governor and Council of the colony ratified the procedure. Soon other tribes were given the same privilege. So anxious were they to dispose of their land when allowed to convey a legal title, that it became necessary for the colony to forbid further land transfers without the Assembly's stamp of approval. Such a step was taken in order to prevent the continual necessity of apportioning new lands to keep the natives satisfied. "By 1658 the Assembly had received from several Indian tribes so many complaints of being deprived of their land, either by force or fraud, that measures were again adopted to protect the natives in their rights. No member of the colony was allowed to occupy lands claimed by the natives without consent from the Governor and Council or from the commissioners of the territory where the settlement was intended. To decrease the chances for cheating the Indians, all sales were to be consummated at quarter courts where unfair purchases could be prevented. "Efforts to protect the Indians in the possession of their lands were subject to modification from time to time. The treaty of 1646 designated the York River as the line to separate the settlements of the English and the natives. But the colony at that time was on the eve of a great period of expansion. With an estimated population of 15,000 in 1650, the colony increased by 1666 to approximately 40,000, and by 1681 to approximately 80,000. To stem the tide of the advancing English settlement was apparently an impossibility. Therefore, Governor William Berkeley and the Council, upon representation from the Burgesses, consented to the opening of the land north of the York and Rappahannock rivers after 1649. At the same time the provision making it a felony for the English to go north of the York was repealed. This turn in policy, based upon the assumption that some intermingling of the white and red men was inevitable, led to the effort to provide for an "equitable division" of land supplemented by attempts to modify the Indian economy which had previously demanded vast areas of the country. " Endeavoring to provide for this 'equitable division' of land, the Assembly in 1658 forbade further grants of lands to any Englishmen whatsoever until the Indians had been allotted a proportion of fifty acres for each bowman. The land for each Indian town was to lie together and to include all waste and unfenced land for the purpose of hunting. This provision did not relieve all pressure on Indian's lands, partly because some of the natives never received their full proportion and partly because some had been accustomed to even larger areas. But it did serve as a basis for reservation of land for different tribes. "Two years later the Assembly in 1660 took definite steps to relieve the pressure of English encroachments upon the territory of the Accomac Indians on the Eastern Shore. Enough land was assigned to the natives of Accomac to afford ample provisions for subsistence over and above the supplies that might be obtained through hunting and fishing. To insure a fair and just distribution of these lands, the Assembly passed over surveyors of the Eastern Shore and required that the work be done by a resident of the mainland, who obviously would be less prejudiced against the aborigines because of personal interest. When once assigned to the natives, the land could not be alienated. " By 1662 this last provision, forbidding the Accomacs to alienate their lands, was extended to all Indians in Virginia. The Assembly had realized that the chief cause of trouble was the encroachment by the whites upon Indian territory. Efforts, therefore, had been made to remove this cause of friction by permitting purchases from the natives provided each sale was publicly announced before a quarter court or the Assembly. But the plan had not been a complete success. Various members of the colony had employed all kinds of ingenious devices to persuade the natives to announce in public their willingness to part with their land. Dishonest interpreters had rendered 'them willing to surrender when indeed they intended to have received a confirmation of their owne rights.' In view of these evil practices the Assembly declared all uture sales to be null and void. "Twenty-eight years later in 1690 the Governor and Council in accord with this restriction nullified several purchases made from the Chickahominy Indians. By order of the assembly in 1660 this tribe had received lands in Pamunkey Neck. Since that time several colonists had either purchased a part of their land or encroached upon their territory without regard for compensation. In neither case were the white settlers allowed to remain. All leases, sales, and other exchanges were declared void by the Governor and Council, and all intruders were ordered to withdraw and burn the buildings that had been constructed. George Pagitor, being one of the settlers affected by this order, had obtained about 1,200 acres in Pamunkey Neck from the natives. He had built a forty-foot tobacco barn and kept two workers there most of the year. When his purchase was declared void, he was ordered to return the land to the natives and to burn the barn that had been constructed. Accompanying this executive decree was an order to the sheriff of New Kent County authorizing him to carry out the will of the officials of the colony and to burn the barn himself, if necessary." 23

To Top of Page and Table of Contents {the Anglo Powhatan Wars] To Topic Top [the 3rd Anglo Powhatan War] and Its Tape of Contents On to The Treaty of October 1677 Further Restricting the Powhatan The Treaty of October 1677 "Opechancanough was succeeded by Necotowance [ed note : signator of the treaty of 1746 ending the third anglo powhatan war severely restricting the territory of the Powhatan people by confining them to small reservations ], son of Powhatan's eldest sister, then by the Queen of Pamunkey [ed note: named Cockacoeske] who was reigning in 1676. In that year, when trouble with northern Indians was threatening, she was invited to Jamestown to confer with the governor and council. The chairman asked her how many men she could furnish the colony in the war that seemed impending. At first she declined to speak, but finally uttered vehement reproaches against the English for their injustice and ingratitude. Her husband, Totopotomoi, had been slain with many of his men while assisting the settlers against the Ricahecreans, and she had never had 'any compensation for her loss.' After further parley, she 'abruptly quitted the room.'" 13 To Top of Page and Table of Contents [The Anglo Powhatan Wars]

Sources For This Page:ld 1. Review by Roy W. Johnson of Jamestown 1544-1699 by Carl Bridenbaugh [New York: Oxford University Press, 1980 ISBN 0-19-502650-0 ] 2. CHRONOLOGY OF INDIAN ACTIVITY [from the National Park Service involving Jamestown] Very brief summation 3. Webcitation found at http://www.geocities.com/bryanmcgirt_uncp/article1.html 4. The Indian Tribes of North Americaby John R. Swanton Virginia Tribes Manahoac through Tutelo. Presented by the website Searching for Saponi Town" 6. History of the Pamunkey Tribe from the Pamunkey Tribe Pages 7.Opechancanough, the massacre of 1622, an excerpt from Volume I of Our County, published in the late 1800s 8. Jamestown Society pages 9.Powhatan Indian Lifeways presented by the National Park Service 10. Helen C. Rountree, Ph.D. Professor Emerita of Anthropology , Old Dominion University , Norfolk, Virginiain her articleIn Helen Rountree's response to Accohannock history found at the New Mexico Genealogical Society's pages. 11.Newsletter Volume 3, Number 4, December 2000 Webpages of the Surry Side Of the Jamestown Settlement Surry County, VA. USA. No author is given. Page mounted by Surry County, Virginia, Historical Society and Museums, Inc 12. Jamestown Interpretive Essays " Sir William Berkeley" by Warren M. Billings, Historian of the Supreme Court of Louisiana and Distinguished Professor of History, University of New Orleans. Virginia Center for Digital History, University of Virginia http://www.iath.virginia.edu/vcdh/jamestown/essays/billings_essay.html 13. In pages of t the University of Virginia American Studies Webpages. Unsourced tour information 14. Martin's Hundred from History.net. "This article was written by J. Frederick Fausz and originally published in American History Magazine in March 1998. " Reprinted under the Fair Use doctrine of international copyright law. 15. Jamestown 1544-1699 by Carl Bridenbaugh [New York: Oxford University Press, 1980 ] 16. The History and Present State of Virginia by Robert Beverly . Edited by Louis B. Wright. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1947. Cited at: 17. In River Time The Way of the James by Ann Woodlief Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1985 . Chapter 5. Reprinted under the Fair Use doctrine of international copyright law. 18. The Church of England, Diocese of Rochester, webpage entitled St George's Church Gravesend. The Story of Princess Pocahontas. 19. Native Americans Post Contact from The Mariners Museum, Newport News, Va pages 20. Powhatan Page of Virtual Jamestown Website 21. A Brief History of Jamestown from the tobacco.org pages 22. Pocohontas Biography part of Biography Project for Schools pages of of AETV. com 23. unsourced entry is presented at Sue Gill's Webpages, with citation: 'Submitted by PACJ1945@aol.com on VA Southside Mailing List, submitted for Gill web page by Sue Gill' . Appears to be anunidentified text. To Page Table of Contents All Pages of Within The Vines are Copyright Protected. See Terms of Use |

|